As Annie Dillard might say, I didn’t write this, I typed it.

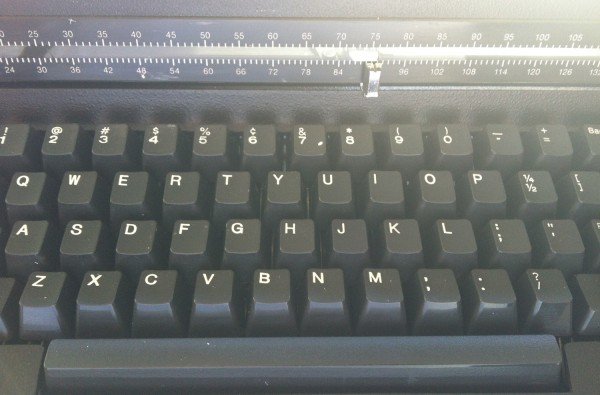

In fact, I typed it on a black 15″ IBM Selectric III — correction, a Correcting Selectric III, which began production, I am informed, in 1980. It’s the one I learned to type on and, I know now, began to learn to write.

Well, not the exact one of course. That was Da’s tan-colored one, in the extra room in the first and last house my parents owned in California, the one he used for a library, which smelled of book must and LPs and Pall Malls, and sat in front of a television. But it’s the same basic model.

So of course I have it now, via the continuous community online garage sale, in part because I had it then. And in part because hey, talk about yer no distractions, try a typewriter! When I was writing in front of the television 30 years ago, for some reason whatever I was watching didn’t hold me up. But now, such things do.

Still those are few of the several reasons.

Biggerly is that I knew right away I’d love having it for those several reasons and here, 199 words in, I know I’m right. Even though I had to transfer it to the computer for anyone to see it — and “doubling” the work will be the least among the crazy things people may think about this exercise.

Ah Well. I can say they’re wrong.

It doesn’t double the work; it does the work. It makes the work more workey. I can feel myself doing the work, and of course I mean that literally. I can feel the keys, texture like constant Braille, or those cottage cheese ceilings of youth. I am remembering the whirhum of it all; the clackety keys, fast and furious as when The Lone Ranger gave chase in my dad’s radio; the cost of a mistake — again literally, if I choose to spend that eighth inch of correcting tape on it, instead of xxxx-ing it out.

I love that on that draft I had to estimate the number of words a moment ago. I love that I can’t italicize. I love that I have to manually underline each word.

I love the Courier font.

Yes I feel how odd all this is.

And I feel how glorious, too.

As I type the draft, I’m imagining re-doing it, and why would I (re) do that; and why would I choose to hit “Return” when I get to the end of each line, though to be honest I more commonly use the “Mar Rel” key and type a few more characters; and why opt to feed a new sheet of paper each time I get to the end of the one I’m on; and why have to sometimes look back to see where my sentence left off; and why deal with drafts where, just as this one just did, when I type “the” I sometimes type so quickly that the “t” and the “h” overlap each other and it looks bad.

Whyever would I choose not only to do less, but to be able to do less? After all, not doing as much with this boxy beast is the understatement, and I do feel it every time I hit “Return” — which having to do at the end of every line will come as a surprise for some time. In addition to minor shocks, I’m going to make mistakes, the kind I can’t readily correct, and I’m going to have to get used to that.

[In the typed draft, that last sentence had two typos and a missing comma.]

What I learned in only one afternoon — or rather, saw because learning will take time — is that one thing all this means is that I can only write — which is what I claim to want. Some days in fact I will, pace Dillard, only type; it will oft be the best I can offer. What I saw is that to hit “Return,” means I must be conscious of doing it, and so of what I’m doing alway. That not being able to auto-correct or backspace without cost means being accustomed to regular error. That all of this taken together means I’ll also get to ! use a pen now and again, because I’ll need to read over what I’ve written.

All goods. All about slowing down, and feeling what I’m doing, and being in my environment rather than trying to control it, and to bend it to me.

There will even be the occasional quirk.

For instance, sometimes, at the end of the line, when I hit the margin, and before I can decide whether to hit “Return” or “Mar Rel,” the Selectric gives me a “-” — that is, a dash. I remember that, also, from learning on that Selectric built during the Reagan Administration, and awaiting each afternoon after school. That dash is what the black beauty does when you try to force a keystroke past the margin, like a horse shying at a barrier, but having to put its hoof down somewhere.

Like the horse, it knows what it’s doing when I do not. So it’s not only limiting me, but sometimes actively resisting. That’s another benefit.

On the draft, there are now two pages to the right of the machine, and the third in it. I’m going to take new clean white 96 brightness sheaves from the ream on my left, run them through the IBM Correcting Selectric III, then set them upside down on my right. That’s what I’ll do, every time. On those upside down pages I can see the shadow of what I’ve typed, and each perfect embossed period at the end of each imperfect sentence.

I won’t become this guy; I’m sure. Though I wouldn’t mind talking with him. But I only want to type. I only want to continue sensing the heft of this machine, sitting in front of it, in the garage, facing the driveway, its thick black cord plugged into the wall. Maybe not just sense it, but even learn it.

The man who sold it to me said he’d worked for IBM for years — I think he said 40 — and that they stopped making the Selectric III in 1988.

I was 19, and just learning, again, how to write.