This is part one of a two-part post on why, some 45 years later, we still watch Columbo. Part two is here. This essay is excerpted from The Columbo Case Files: Season One, found here. Thank you.

*

For my wedding, I asked for and received the Columbo DVD collection. Complete to that point, it ended with the double helping of Seasons Six and Seven, and back copy text touting the guest stars like Kim Cattrall and Ed Begley, Jr. Plus a “captivating conclusion in these final episodes.”

Those “final episodes” aired on TV in 1978. But instead of ending, Columbo kept coming for 25 more years. The last one ran in January 2003.

Altogether, the show aired over 32 years; 35 counting “Prescription: Murder,” made in 1968. One half the biblical “three score and 10” is not, well, half-bad for TV.

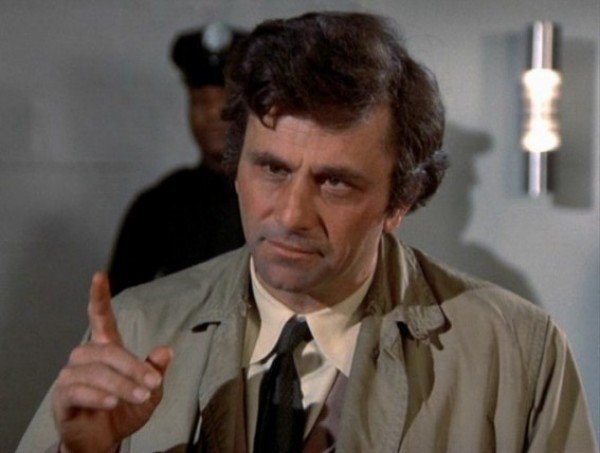

And the Levinson & Link character is even older, dating to a mid-1960s play, and a single episode of a different TV show, with a different actor, in 1960. By then the man who would become iconic — Peter Falk as Lt. Columbo — had already been nominated twice for an Academy Award.

So the show began before I was born, the play is older than my parents’ marriage, and even my dad, who introduced me to the 1970s TV series when I was in elementary school, hadn’t himself graduated from high school by 1960.

Why then do I watch?

Why then do we?

*

When asked why they watch, most people say something about the character “Lt. Columbo.” As so many of the episodes are quite similar to each other — through 35 years of episodes, we’ll see recurring set-ups, returning guest stars (as murderer and/or victim, or even in supporting roles), and sets and backdrops used over and over — this makes sense. After all, if the shows are mainly the same, it’s the character we’re going to be interested in. And people care about people.

So even if it’s the same Universal Studios backlot — where the show was made, and which often played its own role in episodes — and even as we attend a class on the social history of the 1970s, it’s not exactly the same Lt. Columbo. The character develops.

So one thing we’re saying is it’s not just the character “Columbo” but the character of the man.

In fact, when Peter Falk himself was asked why the show endured, he always mentioned people connecting with “the lieutenant” and his homespun ways: his many stories of numberless quirky relatives, his affection for Mrs. Columbo, his never quite ready for prime time rumpled-ness …

He was Everyman … putting away murderers.

*

Of course, there have also been grievous mistakes in supposing why he’s so popular.

For instance, in 1973, when the show was only two years old, a New York Times writer said “the most thoroughgoing satisfaction” of the show was “the assurance that those who dwell in marble and satin, those whose clothes, food, cars and mates are the very best do not deserve it.”

The emphasis is in the original. And it’s not true.

That’s not why we’re satisfied and not why we connect with Columbo the show or Columbo the man. The point is not they don’t deserve it. If we thought that, we’d be judging the killers based on their wealth — supposedly something they do to us.

No.

The point is even the rich are subject to the same laws, moral or otherwise, as we are. This isn’t to say the rich don’t get away with it in real life; in fact, our love for Lt. Columbo affirms this. Because on the show … they don’t get away with it.

Most of us do not begrudge people their money. In fact, in the good news/bad news department, we aspire to it.

But we don’t want them to receive special treatment because of it. And yes, we’ve been known to give them that special treatment ourselves … and yes, we want that money, along with a special life, too … if we ever get that cash.

But the show is there — the lieutenant is there — to remind us it’s wrong.

We don’t care if they own a BMW. But. If they push it off a cliff, with their spouse (already dead) behind the wheel, and pretend it was a kidnapping gone awry, and try to weasel their way out of it, and lie like a bad toupee — we want the bastards nailed.

*

This is part one of a two-part post on why, some 45 years later, we still watch Columbo. Part two follows tomorrow. This essay is excerpted from The Columbo Case Files: Season One, found here and here and here. Thank you.