There is a story from the Johnson Administration which has PBS journalist Bill Moyers, at the time LBJ’s communications director, praying before a meal. With many guests attending, Moyers was at one end of the table and the Leader of the Free World at the other. As Moyers said grace, President Johnson said, “I can’t hear you!”

To which Moyers replied, “I wasn’t talking to you.”

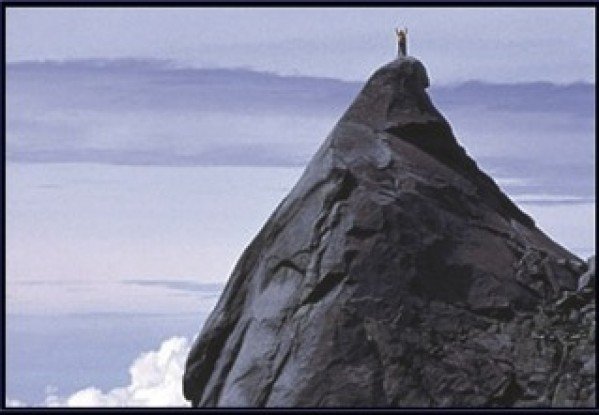

I think this can work in the other direction, as well: there are days when God calls down to us — sometimes in thunder and other times in storm and even betimes in the movement of the posies when there is no wind — I wasn’t talking to you.

This happens often in scripture, of course, when words meant for one person or group — the disciples, or one especially, say; even an entire nation — are transferred without hiccup or hindrance to whomever is reading, or to whom we are speaking, or even preaching. That’s how we get those public notables who otherwise wouldn’t know a command or even throwaway comment of Jesus if it bit them on the ass blathering on about cities on hills, or misquoting condemnatory parables in favor of their preferred tax policy.

Take just one example of this problem, from the New Testament, where Saint Paul says he’s positive God will continue working in the Philippians’ hearts and lives to perfect them until Christ returns.

Now look. OK. The simple fact is that yes, He will continue to work in the hearts and lives of His people until Jesus comes back. He loves us and He’ll do this. But the simple fact before that other one is that in this verse, He wasn’t talking to us.

God will do this because that’s God and what He does, and one reason we know who He is and what He does is scripture. But it’s long bad danger to conflate every verse we read into a direct comment on my life. Here are three quick reasons:

It violates the words — which cannot possibly be directed immediately at me, because I didn’t exist when they were written.

It makes it all about us — when our first task is listen, hear, and try to understand what God is like, and to come to know him.

It inhibits the relationship — that we must have with this God who gave us His words, and yes, is changing our hearts even now.

Yes, scripture is suitable for many things.

Yes, we must internalize, personalize, live it.

Yes, God speaks directly to each of us, in love.

It’s all there, yes. But you have to do the steps, man! It’s something I tried to share with students when they’d read a poem, and the first words out of their mouths were, “What this means to me is … ”

It’s kinda not their fault, and it’s kinda not ours. We’re taught it in our schools, families, jobs, entertainment. We even think it’s humble to say what it means to us, instead of the supposed hubris of believing we can speak into something greater than ourselves.

Sure saves a lot of work, anyway.

But scripture is far more about learning what kind of world this is, what kind of God made it and us, and coming over many millennia to be where we can move freely in it, as freely as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit do right now. We say we want relationship but every time we open up the Bible, we look for explicit marching orders by special telegram to ourselves alone.

Not much of a relationship.

It’s not what the words mean, it’s not all about us, and it’s making relationship impossible. That’s the interesting thing in the Johnson anecdote. He who could not hear grace being said perhaps needed to hear it more than many. But what he needed more was not to hear it.

Because sometimes grace offered directly to (said in front of) the coarsest most needful men is wasted. It only confirms to them what things they think they’ve already heard, when it’s actually been no more to them than the wind in the posies, which they also ignore. Sometimes they need to know the thing they aren’t hearing is something they are also missing.